Why are biologics different?

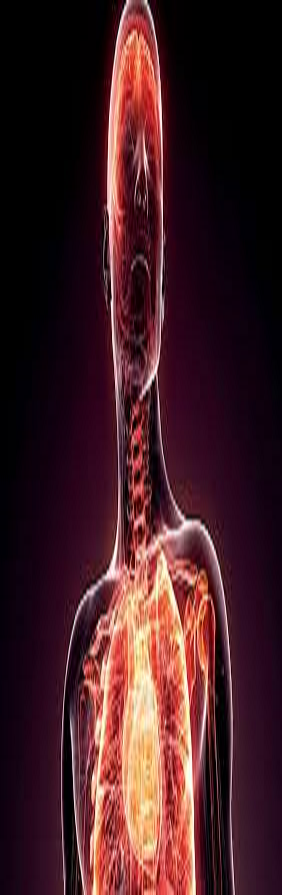

Biologic medicines differ from traditional chemistry-based pharmaceuticals in several key ways

Sources and composition of biologic medicines

Biologics are made from living organisms, including humans, animals, or microorganisms. They are often large, complex molecules like proteins, antibodies, or cells. Unlike traditional pharmaceuticals that are typically made from chemical synthesis, resulting in small, simpler molecules.

The production process

Biologics are produced using biotechnology methods such as recombinant DNA technology, cell culture, and controlled gene expression. Traditional pharmaceuticals are manufactured through chemical reactions and processes in a lab setting.

Structure and complexity

Biologics are large and complex structures with unique three-dimensional shapes. Their complexity often makes them more specific in their action. Traditional pharmaceuticals are smaller, simpler chemical structures.

Mechanism of action

Biologics often target specific components of the immune system or cellular pathways, providing highly targeted treatments. Examples include monoclonal antibodies that bind to specific antigens. Traditional pharmaceuticals generally work by interacting with enzymes, receptors, or other cellular targets to modify biological processes.

Biologics in COPD

Inflammation

COPD is a complex disease with irreversible effects despite optimized treatments. Many patients continue to experience exacerbations that worsen lung function and quality of life. New biologics offer hope, but the early stage of identifying suitable candidates based on inflammation biomarkers may affect the effectiveness of these treatments. Ongoing research into drugs targeting specific inflammatory markers will help define the future use of these new therapies.

Precision Medicine

Over the last few decades, treatments tailored to individual patients have greatly improved outcomes for many diseases. This approach, known as precision medicine, means that treatments are designed based on each patient's unique characteristics, leading to better results with fewer side effects. For these treatments to work best, doctors need to identify specific targets within the disease and select patients who are most likely to benefit, based on certain traits and biological markers.

Most COPD patients have type 1 (T1) inflammation, with neutrophils being the main cells involved. However, up to 40% of patients may also have type 2 (T2) inflammation, with increased eosinophil counts driven by other immune cells. These two types of inflammation can overlap, as seen with the role of IL-13 in COPD, Asthma-COPD Overlap (ACO), and asthma.

Researchers have identified two main COPD phenotypes that might benefit from targeted therapies: the eosinophilic exacerbating phenotype and the non-eosinophilic, predominantly neutrophilic phenotype.

Previously, various monoclonal antibodies targeting specific inflammatory pathways were tested for COPD but didn't show the desired results or had significant side effects.

In respiratory medicine, biologics have been successfully used for conditions like asthma and lung cancer. Recently the FDA, in the United States, has approved dupilumab for COPD with type 2 inflammation.

Considering biologics for my COPD

When considering a biological medication, some important questions to ask are:

- Are my current medications working?

- Do I need to consider different treatment options?

- What biological medications are available to treat my COPD?

- What are the advantages of taking a specific biological medication?

- What are the most common side effects or risks that I need to be aware of?

- Do I need to take any extra precautions when using biologic medicines?

- Can I get this medication through my regular pharmacy?

- What is the process of actually getting the medication?

- How long will I need to be treated with the biologic medication?

Reviewing your exacerbation (flare-up) history with your doctor

- What are the specific triggers that cause your flare-ups?

- When you have a moderate to severe episode, what do you experience?

- Do you report each flare-up with your doctor?

- Have you been hospitalized because of an exacerbation?

- How often do these episodes occur?

- Is the frequency increasing, decreasing or about the same?

Be prepared to talk to your doctor about:

- Your history with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- The options available to you if your condition is getting worse over time

- Discuss specific medication and treatment options available to you

- Review what has worked well, not so well, and the new biological medications that may be appropriate for you

- Talk with you about the risks and benefits of treatment with biologics, including:

- Are you comfortable getting injections?

- Are you comfortable giving yourself an injection?

- Do you have transportation to get to the office regularly for treatment?”

- How much will this cost?

- Is the cost typically covered by public health plans?

- What about private insurerers? Do they cover these injections?

Immunosuppressant and Immunomodulator Medications

The terms immunosuppressant and immunomodulator both refer to medications that affect the immune system, but they do so in different ways and are used for slightly different purposes.

Here's a breakdown of the key differences:

Immunosuppressants

Definition: Medications that broadly suppress or dampen the activity of the immune system.

Primary Purpose: To prevent the immune system from attacking the body (autoimmunity) or rejecting transplanted organs.

Common Uses: Organ transplantation (e.g., kidney, liver); Autoimmune diseases (e.g., lupus, rheumatoid arthritis); Inflammatory conditions

Examples: Cyclosporine, Tacrolimus, Azathioprine, Mycophenolate mofetil, Prednisone (a corticosteroid)

Mechanism: Typically inhibit T-cell activity or other broad immune functions, often affecting both the innate and adaptive immune responses.

Risks: Increased risk of infections (e.g., pneumonia); Higher cancer risk (especially lymphoma or skin cancers); Liver or kidney toxicity

Immunomodulators

Definition: Medications or agents that adjust or modulate the immune response, either by enhancing or suppressing specific aspects.

Primary Purpose:To bring the immune system back to a more balanced or normal state, rather than shutting it down entirely.

Common Uses: Autoimmune and inflammatory diseases; Allergies; Some cancers

Examples: Methotrexate (also considered an immunosuppressant in higher doses); Interferons (e.g., interferon beta for MS); TNF inhibitors (e.g., infliximab, adalimumab)

Mechanism: Target specific pathways or cells (e.g., cytokines, T-cells, B-cells), often more selectively than immunosuppressants.

Risks: May still cause infection risk, but often with a lower systemic impact; Some increase in cancer risk depending on the agent

Immunomodulators in COPD

This area is evolving and more targeted. Use sometimes overlaps with asthma-COPD.

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) A form of local immunomodulation, not true systemic suppression. Used in moderate to severe COPD, especially if the patient has:

- Frequent exacerbations

- Elevated blood eosinophils (>300 cells/µL)

- Features overlapping with asthma

Roflumilast A phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) inhibitor. Reduces inflammation in the lungs (especially neutrophilic inflammation).Technically an immunomodulator—used in severe COPD with chronic bronchitis phenotype and a history of exacerbations

Biologics Typically used in eosinophilic asthma and for COPD with high eosinophils (≥300 cells/μl). Anti-IL 4, anti-IL-5, anti-IL 14 or anti-IgE agents). Examples: dupilumab (Dupixent) and mepolizumab (Nucala)

Easy way to remember

Immunosuppressants = “Turn the immune system way down.”

Immunomodulators = “Fine-tune or rebalance the immune system.”